Sony released the original PSP back in 2005. It was promoted as a portable PS2 but although it was impressively powerful for the time, as was standard practice back then, Sony was talking bollocks and in reality its power lay somewhere between that and a PS1.

Its games came on a Universal Media Disc or UMD. This was a 1.8GB disc encased in a plastic housing that was designed to protect the media from scratches.

UMDs were chosen over cartridges because of their capacity and, more importantly, their cost-per-GB. To compare, cartridges for Nintendo’s DS ranged between 8 and 512MB in capacity – with most games using either 64MB or 128MB.

In truth though, the format sucked. The PSP’s drives were painfully slow, clunky and overly fragile for a console that was meant to be portable. And thanks to the mechanical aspect of the drive, it also impacted on the battery performance of the console.

Sony released two more iterations of this design which improved the performance and specification of the console, but they were all hamstrung by the UMD drive.

In 2009, Sony released the PSP Go. This model removed the UMD drive and the idea was that users would get their games from the online store instead. The removal of the drive meant that the console could be much smaller and lighter than all the other iterations, with better battery life.

Where Sony gave with one hand though, it took away with the other. The memory format was changed from the Pro Duo of the earlier models to another proprietary format called M2, which was much smaller – about the same size as Micro SD. This decision would be significant for the model’s future.

After releasing a console that could only get its games from the online store, Sony seemed determined to make it as difficult and as unpalatable as possible for people to actually go ahead and make use of it:

- The digital versions of games were more expensive than their physical counterparts. They would also remain full price for months if not years after release, while physical copies would get discounts just weeks later.

- Since digital seemed to be an afterthought as far as the PSP was concerned, the vast majority of the PSP’s game library was not available for digital purchase due to licensing issues.

- The M2 memory cards required to store these downloaded games were stupidly expensive compared to alternatives like Micro SD, and while Micro SD capacities continued to increase, the largest M2 that was ever released was just 16GB. This meant users with large collections of digital games would either need to purchase multiple cards – each stupidly expensive – and swap between them as required, or just have the one card with a small selection of games carefully chosen from their online library.

- Although Sony had previously suggested PSP owners with existing UMD collections may be able to trade these in for digital versions at “participating stores”, this idea never came to pass. So regardless of the size of a user’s UMD collection from earlier PSP models, it was actually impossible for Go owners to play those games on the Go without re-purchasing them digitally – for inflated prices – and that was only if they were even available for purchase.

It’s little wonder then that commercially, the Go was a failure.

The hacking scene however turned the Go into a pretty reasonable device, since custom firmware allowed it to run games that the user could either dump themselves using a UMD-based console, or take advantage of someone else’s efforts and download them for free from the internet.

Suddenly the Go wasn’t limited to the anaemic selection of games that Sony had made available on its store, and it could play every game that had been released physically. This really made up for Sony’s poor efforts.

This development benefitted the other PSPs too, since they no longer had to use their slow, clunky and battery-sapping UMD drives to play games but instead could run them all from memory card. However, while those consoles enjoyed ever-expanding Pro Duo capacities, the Go languished on 16GB (or 32GB including the internal memory) and this was because the Go’s lack of sales convinced them not to bother releasing any larger capacities.

The older PSPs have even able to enjoy the much larger capacities of modern Micro SD cards thanks to Pro Duo/Micro SD card adaptors. But since M2 is about the same size as Micro SD, it has not been possible to create an adaptor for those.

The PSP Go is actually my favourite form factor as it fits very comfortably in even the smallest of pockets, and since the screen is a little smaller than it is on the others it also looks a little sharper. It can also be played on a large TV thanks to TV-out and Bluetooth support that allows it to be paired with a controller. For years though, the problem with the Go has been its terribly small memory limitations. But not any more!

Breaking free from M2

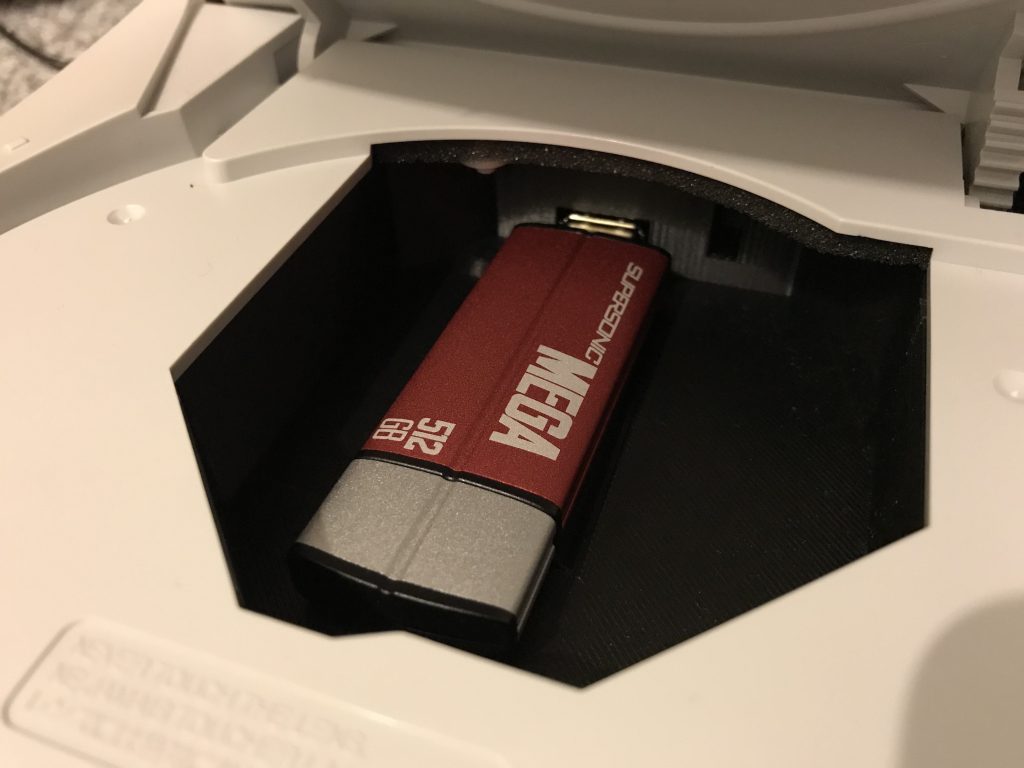

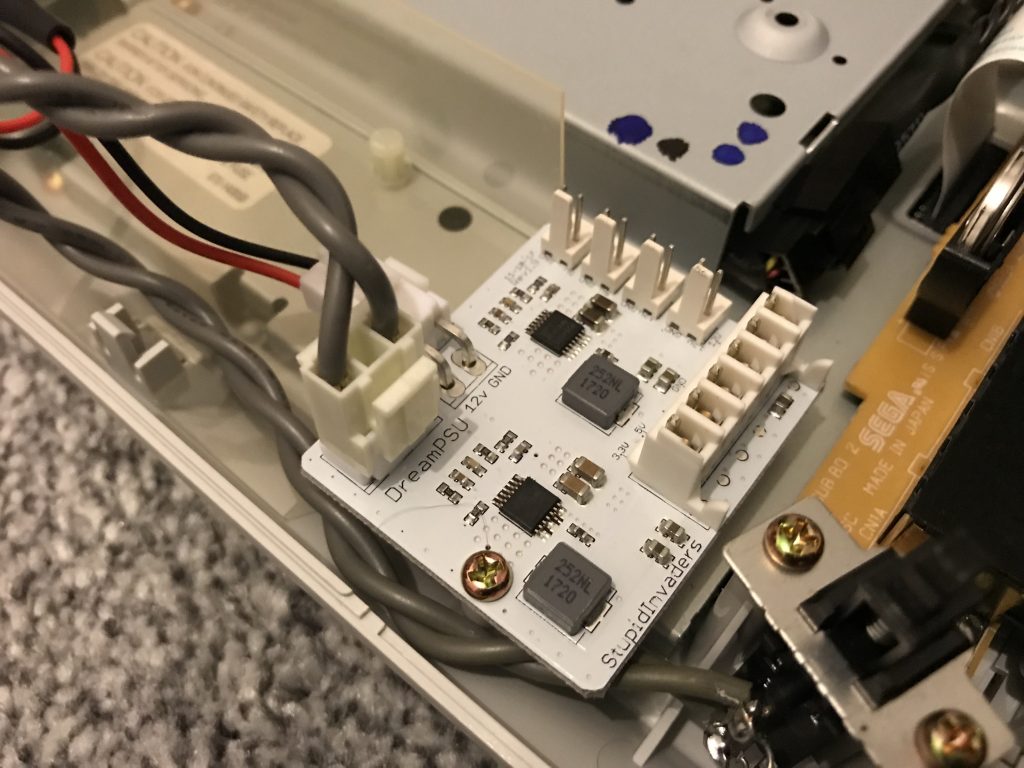

I recently purchased this ribbon cable from a seller in Japan. It allows the use of a Pro Duo/Micro SD adaptor by running a cable from an internally-stored adaptor to the M2 port.

It took about a week to arrive. I’ve just installed it and am pleased to report that my Go now has access to the 16GB internal memory in addition to… a 400GB Micro SD card! So I now have the most portable iteration of the PSP with almost half a terabyte of storage space – and it can even be upgraded with a larger Micro SD card in future as capacities continue to increase!

Similar mods have been available in the past but those have required irreversible modifications to the device, which I was never keen to do. This modification however is completely reversible as it has caused zero harm to the console.

My next problem is deciding on how to fill that card!